By David Barr My sociologist friend, Sam, has a great illustration about the persistent effects of racism: he asks his students to imagine that they are watching a game of Monopoly and one player (let’s say the Thimble) is not allowed to buy property for the first five turns, but does pay rent, while everyone else plays under the normal rules, snatching up several of the best properties. Sam asks his students to imagine they are put in charge of the game after the fifth turn and asks them to think about the best way to make sure the game will be fair going forward.

0 Comments

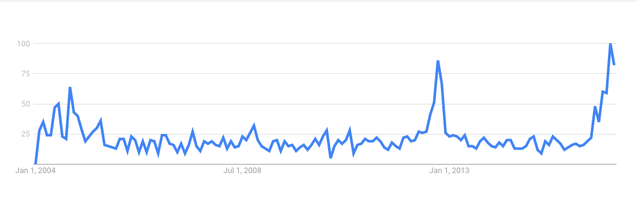

By Russell Johnson President Trump recently announced that there would be a fifty-four-billion dollar decrease in spending on non-defense programs like foreign aid, the EPA, and domestic agencies. This is in keeping with his campaign promises about fiscal responsibility and working toward paying off the national debt. As President Trump said, "With 20 trillion dollars in debt, the government must learn to tighten its belt.” It is also in keeping with Trump’s repeated claims that President Obama’s spending was suicidally excessive, and that his administration would be leaner and do more with less. But at the same time, Trump promised a fifty-four-billion dollar increase in the defense budget. So we won’t actually be saving any money, merely redirecting it. The fact that the numbers are the same indicates that this is a highly symbolic act, and it tells us something about the state of the two major parties in America—namely that they disagree about the shape of government, not the size.  By David Barr Questions of capitalism and socialism, if they ever truly went away, came roaring back into the public conversation during the 2016 election. With them came misunderstandings about what these terms mean, and about American history. It seems to me that when liberals (particularly young ones) say ‘socialism’, they have something like contemporary Scandinavia in mind; open, educated, democratic, and with the highest quality of life in the world. When conservatives (especially older ones) hear ‘socialism’, they think of the USSR or North Korea: repressive, totalitarian, and with inefficient economies that collapsed under the weight of oppressive government control. This obviously leads to lots of head shaking by each group at the seemingly unreasonable beliefs of the other. That phenomenon is certainly worth a post of its own. Right now, however, I’m just going to use the fact that many conservatives interpret 'socialism' in terms from the Cold War as an excuse to make a point about capitalism and communism. I had been pretty sure that nobody wanted to read what I've been thinking about these old Cold War debates, but they seem relevant now that it is clear that those debates still hang over our current ones. I’m now convinced that taking you on a few minutes’ excursion into the mindset of the 1950s can help bring light to our contemporary political conversations. The lesson of the Cold War, I believe, is that the capitalists and the communists were both right…about each other. Let me explain: We recently had a chance to talk with Bert Phillips on his podcast, HearingUS. The wide-ranging interview covers many of the topics familiar to readers of this blog. We focus particularly on what we take to be common sources of disagreement and misunderstanding about religion and politics and what ethical mindsets and habits we think might help.

The podcast can be streamed here or downloaded from iTunes here.  “Not that I condone fascism; or any –ism for that matter. –Isms, in my opinion, are not good. A person should not believe in an –ism, he should believe in himself.” This quotation, from Ferris Bueller, seems like the natural place to begin when trying to define “Trumpism.” It is very important that we have the term “Trumpism” to distinguish Donald Trump’s views from the coalition of views that make up the Republican Party. Though it certainly didn’t emerge in a vacuum, Trumpism is different from the more familiar –isms of the American right. That is to say, it's not the same as:

So what is Trumpism? It is worth noting at the outset that Trumpism is not the product of only one mind, and that the Trump administration has a lot of different ideological voices setting the agenda. But arguably the best place to start is with the man himself, so I read Trump’s 2011 book Time to Get Tough. What follows is a summary of what I learned.  by Russell Johnson In defense of the recent executive order about immigration, Senator Steve Daines wrote, “We are at war with Islamic extremists and anything less than 100 percent verification of these refugees’ backgrounds puts our national security at risk. We need to take the time to examine our existing programs to ensure terrorists aren't entering our country. The safety of U.S. citizens must be our No. 1 priority.” No doubt, the Senator expresses what many in our country are thinking. There is much to be said, and much that has been said, about the effectiveness and rationality of this particular executive order. But I’d like to focus on two truths we must not forget: No matter what we do, innocent Americans are going to die. But there are fates worse than death.  Much has been written about our polarization in values and ideologies, and now much more has been added about our different sources of information and “alternative facts.” This post focuses on another important, but neglected, area of divergence and source of disagreement: the myths we tell that form the context of the values we hold and the facts we accept. My hope is that pointing to myths as an arena of misunderstanding can provide a path forward in cases where agreement and empathy seem impossible.  I can’t stand it when people have their headphones up loud in public places. What’s the point of wearing headphones if everyone around you on the plane can hear your music? Now I’m distracted by your music and I’m distracted because I’m worried about the damage you’re doing to your ears. It’s frustrating… …but not as frustrating as terrorism. For you see, no matter how bad something is, there is always something worse. Or so it seems according to the popular rhetorical move I call the “hypocrisy juke.” It goes like this: a person or group protests something, and then someone else dismisses them and calls them a hypocrite because they aren’t protesting another, different thing. (By “protest,” I mean anything from marching with signs to posting about it on social media.) Here are a few examples:  There is a longstanding view that people all have access to the same facts and their political differences are due to different moral values. This may never have been true, but at the very least it is an inadequate framework for understanding contemporary political disagreements. C.S. Lewis was once presented with an argument for moral progress. We must have developed better moral principles, he was told, since years ago there were witch-burnings but nowadays the majority of Englishmen finds this practice ghastly. His response is instructive: “But surely the reason we do not execute witches is that we do not believe there are such things. If we did—if we really thought that there were people going about who had sold themselves to the devil and received supernatural powers from him in return and were using these powers to kill their neighbors or drive them mad or bring bad weather, surely we would agree that if anyone deserved the death penalty, then these filthy quislings did.” He then spells out his point more precisely, “There is no difference of moral principle here: the difference is simply about matter of fact.”[1] Those who burn witches and those who don’t, according to Lewis, differ more in their beliefs about what is the case than in their moral values. Many of the disagreements tearing Americans apart this election cycle are differences not of principles but of facts.  A reading from the Psalms: "The heavens declare the glory of God, and the sky above proclaims his handiwork. Day to day pours out speech, and night to night reveals knowledge.” Psalm 19:1-2 In at least one sense, science is the original human vocation, a call to share with God in his wonder-filled attention to his creation. In Genesis, we see that as God creates, he calls the different things he makes “good.” When creation is finished and God beholds “everything that he had made,” he declares it “very good.” Then he does something remarkable. He places his final creation—Adam—in the Garden of Eden and gives him a task: to name each creature. Thus, God not only rejoices in the goodness of his creative work, he creates beings who can share in knowing and appreciating it in its particularities. Thus, we see that the original, pure communion between God and man is focused, not in on the relationship between the two of them as individuals, but out toward all creation.  Russell (RPJ): I read an interesting article recently from The Washington Post that explained, better than any article I’ve ever read, one important way conservatives and liberals talk past one another. It’s by David Hopkins and Matt Grossmann, who surprisingly aren’t quarterbacks for the Cleveland Browns. It’s worth reading if you have the time, but I’ll summarize their main point now. If you read the article, feel free to skip this summary. These two professors write that Republicans and Democrats in America think differently not just about the issues, but about how to frame the issues. “Each party’s supporters define the terms and stakes of political competition quite differently,” they write, “Republicans believe they’re battling over two opposing ideologies, while Democrats view partisan conflict instead as a fight between different social groups.” Republicans are more likely to think in terms of conservatism vs. liberalism, socialism vs. capitalism, traditional values vs. postmodern multiculturalism. Democrats are more likely to think in terms of men and women, black and white people, the one percent and the ninety-nine percent.  What do we mean when we say “America”? This is a more complicated question than it first appears. To answer it, of course, we need to talk about football. During the NFL preseason, most professional football players are focused on only one thing: not tearing their ACLs. But this year, Colin Kaepernick caused an uproar for choosing to sit during the national anthem. As he said in interviews, he is disheartened and incensed by racial prejudice in America, in particular with regard to police brutality. “This country stands for freedom, liberty, justice for all,” Kaepernick said, “And it’s not happening for all right now.” Unsurprisingly, there has been considerable backlash against Kaepernick for this, principally asserting that it is an act of disrespect against America and American veterans. Equally unsurprisingly, there has been backlash against the backlash and protests against the protests. For the moment, I’m not going to protest anything. I simply want to use this as an opportunity to point out a rhetorical effect at play in the conversation.  by Russell Johnson It’s only August, but we already know who TIME Magazine’s Person of the Year will be. It’s not Simone Biles, it’s not Elon Musk, and it’s not Pikachu. No, in 2016 no one has been in America’s spotlight more than Donald Trump, and it’s not even close. He has been protested, praised, scrutinized, reviled, endorsed, criticized, quoted, and parodied more than anyone. He is the tap on the knee to which everyone immediately reacts. If 2016 were a novel, Trump would be the main character, and every other character would take their place in relation to him. It’s hard to overstate the widespread obsession with Trump which has captured the imagination of pundits, news media, and bloggers, especially those on the left. The pull is hard to escape—there’s just so much to say about him. There are so many things to criticize; scholars, artists, and comedians are relishing in the opportunity to unload their full critical arsenal. Finally there is a villain deserving our smug liberal heroics. So we enlist in the war of everyone versus Trump. And as so often happens in wartime, we violate the very principles for which we fight. Some of the casualties of 2016 have been objectivity, charitable interpretation, tolerance, a cooperative approach to governance, and even basic respect.  [ While there's no need to have read my previous post to read this one, folks who have will recognize that this is the second of two posts in response to the claim that the best strategy to end violence on the south and west sides of Chicago is the spread of the gospel through evangelism. -David] If we are going to think about evangelism as a strategy to fix the problem of violence in Chicago, it makes sense to begin with the question: is a lack of knowledge of the gospel the cause of the shootings among young black men in Chicago? Well, it’s certainly clear that the absence of Christianity cannot cause shootings in the way we talk about one billiard ball causing another ball to move. It cannot be simple cause and effect. If it were, all non-Christians would be shooting people all the time. It would be hard to explain how, for example, Japan is only 2% Christian but has one of the lowest murder rates in the world.  by Russell Johnson Clint Eastwood was in the news this week, not for remaking Denzel Washington’s “Flight,” but for some comments he grumbled angrily during an interview with Esquire. When asked about Donald Trump in an interview, Eastwood said, “He’s onto something, because secretly everybody’s getting tired of political correctness, kissing up. That’s the kiss-ass generation we’re in right now. We’re really in a p**** generation. Everybody’s walking on eggshells. We see people accusing people of being racist and all kinds of stuff. When I grew up, those things weren’t called racist.”  I recently heard a Christian speaker talk about violence in Chicago. According to him, the answer to the problems plaguing the south and west sides of the city is simple: these communities need to embrace the Gospel. This is not an unusual way for Christians to think, of course, and it might seem to flow from some of the central tenets of the faith. Becoming Christian should make people better, right? If enough people are transformed, that should make neighborhoods better, too. Plus, we look around our churches and see a bunch of (mostly) nice, smiling people who seem unlikely to commit murder. It is only reasonable, then, to think that if we could only bring enough of our neighbors into the Church and into faith, then a host of societal problems would be solved. While I understand the temptation to think this way, I'm increasingly convinced that this is not how Christians should think and talk about social problems.  (Photo: DonkeyHotey) (Photo: DonkeyHotey) Welcome to our first ever FTSOA chat! What follows is a free-flowing discussion between Russell, David, and Mike Lehmann, a Republican political operative with a Duke Divinity School degree and friend of the program. This conversation has been slightly edited for clarity. DAVID: I hear lots of people talking about the choice between Trump and Clinton as picking between “the lesser of two evils” and many seem conflicted about doing that. But what is the moral significance of voting for an objectionable presidential candidate? Are you morally on the hook for the candidate’s full slate of positions? Should your conscience hold you back?  This election, Americans are choosing between two incredibly unpopular candidates. According to surveys, both Hillary Clinton and Donald Trump have 37% approval ratings. To put that in Rotten Tomatoes terms, they both have the same approval rating as “Bicentennial Man” and “Scary Movie 4” (and, perhaps ominously, “The Purge.”) Americans, by and large, are not thrilled to vote for the two people who have a legitimate chance at winning. The primary process of the two major parties has left us feeling at a loss. We’d rather vote for someone else—ideally Terry Crews, but frankly at this point we’d settle. So we turn our attention to Jill Stein and Gary Johnson, who like many third party candidates before them are fully prepared to suggest sweeping-but-impractical-sounding reforms to take advantage of our disappointment in the Republicans and Democrats. They have to overcome two hurdles—first, convincing voters that they’re well-qualified to be president, and second, convincing those same voters that a third party vote isn't “throwing away your vote.” Even in an electoral year like this one, when the two major candidates have worse approval ratings than Comcast and Time Warner Cable, third party candidates may be able to overcome the quality hurdle but not the viability hurdle. Let’s think for a second about why.  Michelle Obama mentioned in her DNC speech that the White House was built by slaves. Bill O’Reilly then announced on his show that he had looked it up and reassured his viewers that the "slaves that worked there were well fed and had decent lodgings provided by the government, which stopped hiring slave labor in 1802.” People were justifiably angry with O’Reilly over this. It came across like he was saying, “Yeah, ok, I admit the U.S. government used slaves in the past, but it wasn’t that bad and we stopped doing it right away. We can all keep our faith in America’s moral purity.” His comment and the backlash got me thinking about the defensiveness on all sides here. O’Reilly and others of his ilk have very little patience for criticism of America’s past greatness, what they call “revisionist” history. Since America is clearly great, to point out its foibles and imperfections is to obscure the issue, when (to them) America's greatness is clear. Likewise, folks who think slavery and its legacy are a really big deal have very little patience for people pointing out the times it wasn’t so bad. Since slavery was clearly an abomination, to bring up mitigating examples of humane treatment of slaves is (to them) to obscure the verdict of history.  Earlier this week, Wayne Grudem endorsed Donald Trump. You may be thinking, “Big deal. I bet a lot of people named Wayne endorsed Donald Trump.” But Wayne Grudem is different. He’s the author of the systematic theology book used by more evangelical seminaries than any other. It’s currently listed as the #1 bestselling Protestant theology book on Amazon.com, and the #1 bestselling systematic theology book. Grudem has been influential among evangelicals for decades now; his writing and teaching form the intellectual backbone of many pastors’ and writers’ theologies. His article, “Why Voting for Donald Trump Is a Morally Good Choice” feels to many of my fellow evangelicals as a betrayal. Though it was scarcely surprising that public evangelicals like Jerry Falwell Jr. and Franklin Graham—whose names are bigger than their influence—supported Trump, it hurts to see  The other day my friend told me something I’ve heard from many Christians over the years. He said, “As a Christian I think it is the church’s job to help the poor, not the government’s.” While this sentence has a nice, reassuring neatness, it is actually a pretty problematic way to talk about politics “as a Christian.” To see why this is the case, consider first the “as a Christian, I think” part of his statement. Now, obviously, we can think a lot of things "as Christians." To name three, we could think that Christians should love their neighbors, that the death penalty is wrong, or that pizza is delicious. It is clear that thinking of them “as a Christian” means something different in each case.  What does it mean to be conservative? Conservatism as a political philosophy is rooted in the “test of time.” The best guide for present action is past experience. Its core principle is that the best political system is one that reflects human nature, and the best resource for understanding human nature is the record of history. Put your trust not in what “should work” according to an abstract theory, but first and foremost in what “has worked” in real life. So conservatism is not against progress; rather, conservatism is against naïve idealism. A conservative is open to new ideas, but those new ideas need to be justified in the light of the accumulated wisdom of the centuries. Conservatism is “Just the facts, ma’am.” It’s “That’s all fine in theory, but how does it work in practice?” It’s “Those who fail to learn from history are doomed to repeat it.  [Originally posted on Facebook on 2/12/16] Dear haters of Beyoncé's Super Bowl performance, No. I'll be more specific. Many people have criticized Beyoncé and her dancers for dressing up in outfits reminiscent of the Black Panthers from the 60s and 70s. So people are upset because Beyoncé is representing a group with a violent history at an NFL game? The same NFL that has a team called the Vikings? And one called the Raiders? And the Buccaneers? And, while we're at it, one called the Texans? But whatever, I'll let it slide. I for one think Beyoncé can reasonably laud the Black Panther Party's commitment to organize against police brutality without thereby endorsing all of the actions taken by its members. But there's room for argument.  The whole “Trump is a fascist” thing is a little overblown, I think. He is the sorcerer’s apprentice of fascism, not nearly coherent or profound enough to guide or control what he has unleashed, so I don’t mean to say anything close to “Trump is Hitler.” Rather, I think he has failed to learn the lessons that fascism ought to have taught us. The mistake of theirs that he repeats is that, like fascists and other reactionaries, he has no solutions to the problems of a diversifying society in a complex global age and can only dream of forcing a return to an idealized, fictional past in which he thinks these problems didn’t exist. |

Archives

September 2020

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed