By Russell Johnson Political discourse is plagued by false either/ors. While there are sometimes mutually exclusive options (e.g., should we pass this law, or shouldn’t we?), people typically whittle complicated issues into simple dichotomies that distort more than they clarify. We often find ourselves in debates that aren’t about mutually exclusive options at all—Should we change abortion laws, or support would-be single mothers to make abortions less common? Should we protect free speech, or resist bigotry? Should we make sure everyone has access to good schools, or allow parents to choose where their children learn? I mean, why not both, right? That having been said, saying “Why not both?” always feels to me like a bit of a cop-out. To simply acknowledge that there are good points on both sides of a debate, or to insist that competing plans aren’t mutually exclusive, can be a lazy way of avoiding the difficult questions that give rise to the debate. “Why not both?” can be an excuse to stay on the sidelines, self-satisfied with one’s own enlightened detachment from any particular solution. I think “Why not both?” is important to remember, but not if it’s used to dismiss the need for commitment. It has a place in the conversation, but it can’t be the last word. One way to go beyond false dichotomies and beyond “why not both?” is to think in terms of the many factors that go into solving any complex problems. We have to think algebraically.

1 Comment

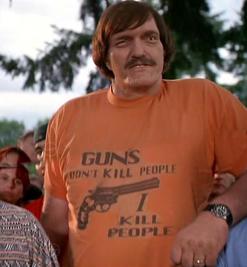

by Russell Johnson Gun control is one of the most frequently talked about political issues in America, but these interactions rarely seem to change people’s minds. This might be true even of the most thoughtful, reasonable discussions, but the gun debate has been characterized by bad arguments that we should never expect to change anyone’s mind. This is often because representatives of one perspective caricature and misunderstand the logic behind other perspectives, so we end up arguing against positions that few people, if any, really hold. The more we rely on these shallow arguments, the more we insulate ourselves in bubbles, making it harder for us to understand one another and harder to seek the truth. In this post, I’ll survey nine all-too-common arguments, from "both sides," that we can safely retire.  Today marks the fiftieth anniversary of the My Lai Massacre. It's worth taking a moment today to reflect on this event, what it tells us about war and what it tells us about ourselves. Here's a blog post Russell wrote for the Political Theology Network reflecting on My Lai and how the dangers of dehumanization extend even into our everyday political discourse.  By Russell Johnson for Martin Luther King Day, 2018 Even as an elementary school student, I knew Martin Luther King Jr. took a stand for integration. But what “integration” meant for King is something I’ve only recently begun to understand. Integration must first be distinguished from inversion. King was not interested in merely transferring power from whites to blacks while keeping the exploitative power structure unchanged. An unjust society cannot be integrated, regardless of the color of those in charge.  By Russell Johnson I once read about a woman who tried to send an email to an accounting firm that said, “I am afraid that we will have to postpone our meeting.” But she hit ‘send’ prematurely, and all the email said was: “Hi Jeffrey, I am afraid” This sort of thing happens to all of us. This week, it happened to President Trump. Shortly after midnight, Trump tweeted, “Despite the constant negative press covfefe”. Everyone immediately recognized that he was trying to type “coverage” and slipped up. He made a typo on social media and hit send before fixing it, which again is not a big deal, even for a sitting president. People had a lot of fun with “covfefe,” but it is a human mistake, maybe even an endearing mistake, for the President to make. But then…  By Russell Johnson Leading up to Lady Gaga’s Super Bowl performance, countless bloggers wondered about whether or not she would “go political,” and whether or not she should. After her performance, many debated whether or not it was “political,” including one memorable op-ed that argued precisely by being apolitical she made the perfect political statement. Classic Gaga. We’ve all heard people get frustrated when a TV show gets political or a company makes a political statement or a Facebook friend makes too many political posts. The general sense is that in these contexts one should stay non-political and if one does address politics, one should do so in a non-partisan way (e.g. saying “make your voice heard, get out and vote” is fine, but telling people how they should vote isn't).  “Not that I condone fascism; or any –ism for that matter. –Isms, in my opinion, are not good. A person should not believe in an –ism, he should believe in himself.” This quotation, from Ferris Bueller, seems like the natural place to begin when trying to define “Trumpism.” It is very important that we have the term “Trumpism” to distinguish Donald Trump’s views from the coalition of views that make up the Republican Party. Though it certainly didn’t emerge in a vacuum, Trumpism is different from the more familiar –isms of the American right. That is to say, it's not the same as:

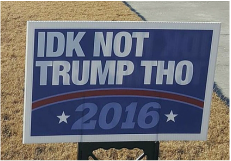

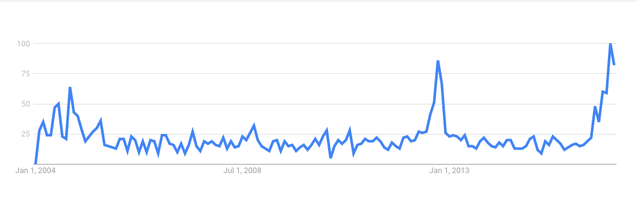

So what is Trumpism? It is worth noting at the outset that Trumpism is not the product of only one mind, and that the Trump administration has a lot of different ideological voices setting the agenda. But arguably the best place to start is with the man himself, so I read Trump’s 2011 book Time to Get Tough. What follows is a summary of what I learned.  by Russell Johnson In defense of the recent executive order about immigration, Senator Steve Daines wrote, “We are at war with Islamic extremists and anything less than 100 percent verification of these refugees’ backgrounds puts our national security at risk. We need to take the time to examine our existing programs to ensure terrorists aren't entering our country. The safety of U.S. citizens must be our No. 1 priority.” No doubt, the Senator expresses what many in our country are thinking. There is much to be said, and much that has been said, about the effectiveness and rationality of this particular executive order. But I’d like to focus on two truths we must not forget: No matter what we do, innocent Americans are going to die. But there are fates worse than death.  I can’t stand it when people have their headphones up loud in public places. What’s the point of wearing headphones if everyone around you on the plane can hear your music? Now I’m distracted by your music and I’m distracted because I’m worried about the damage you’re doing to your ears. It’s frustrating… …but not as frustrating as terrorism. For you see, no matter how bad something is, there is always something worse. Or so it seems according to the popular rhetorical move I call the “hypocrisy juke.” It goes like this: a person or group protests something, and then someone else dismisses them and calls them a hypocrite because they aren’t protesting another, different thing. (By “protest,” I mean anything from marching with signs to posting about it on social media.) Here are a few examples:  There is a longstanding view that people all have access to the same facts and their political differences are due to different moral values. This may never have been true, but at the very least it is an inadequate framework for understanding contemporary political disagreements. C.S. Lewis was once presented with an argument for moral progress. We must have developed better moral principles, he was told, since years ago there were witch-burnings but nowadays the majority of Englishmen finds this practice ghastly. His response is instructive: “But surely the reason we do not execute witches is that we do not believe there are such things. If we did—if we really thought that there were people going about who had sold themselves to the devil and received supernatural powers from him in return and were using these powers to kill their neighbors or drive them mad or bring bad weather, surely we would agree that if anyone deserved the death penalty, then these filthy quislings did.” He then spells out his point more precisely, “There is no difference of moral principle here: the difference is simply about matter of fact.”[1] Those who burn witches and those who don’t, according to Lewis, differ more in their beliefs about what is the case than in their moral values. Many of the disagreements tearing Americans apart this election cycle are differences not of principles but of facts.  Russell (RPJ): I read an interesting article recently from The Washington Post that explained, better than any article I’ve ever read, one important way conservatives and liberals talk past one another. It’s by David Hopkins and Matt Grossmann, who surprisingly aren’t quarterbacks for the Cleveland Browns. It’s worth reading if you have the time, but I’ll summarize their main point now. If you read the article, feel free to skip this summary. These two professors write that Republicans and Democrats in America think differently not just about the issues, but about how to frame the issues. “Each party’s supporters define the terms and stakes of political competition quite differently,” they write, “Republicans believe they’re battling over two opposing ideologies, while Democrats view partisan conflict instead as a fight between different social groups.” Republicans are more likely to think in terms of conservatism vs. liberalism, socialism vs. capitalism, traditional values vs. postmodern multiculturalism. Democrats are more likely to think in terms of men and women, black and white people, the one percent and the ninety-nine percent.  What do we mean when we say “America”? This is a more complicated question than it first appears. To answer it, of course, we need to talk about football. During the NFL preseason, most professional football players are focused on only one thing: not tearing their ACLs. But this year, Colin Kaepernick caused an uproar for choosing to sit during the national anthem. As he said in interviews, he is disheartened and incensed by racial prejudice in America, in particular with regard to police brutality. “This country stands for freedom, liberty, justice for all,” Kaepernick said, “And it’s not happening for all right now.” Unsurprisingly, there has been considerable backlash against Kaepernick for this, principally asserting that it is an act of disrespect against America and American veterans. Equally unsurprisingly, there has been backlash against the backlash and protests against the protests. For the moment, I’m not going to protest anything. I simply want to use this as an opportunity to point out a rhetorical effect at play in the conversation.  by Russell Johnson It’s only August, but we already know who TIME Magazine’s Person of the Year will be. It’s not Simone Biles, it’s not Elon Musk, and it’s not Pikachu. No, in 2016 no one has been in America’s spotlight more than Donald Trump, and it’s not even close. He has been protested, praised, scrutinized, reviled, endorsed, criticized, quoted, and parodied more than anyone. He is the tap on the knee to which everyone immediately reacts. If 2016 were a novel, Trump would be the main character, and every other character would take their place in relation to him. It’s hard to overstate the widespread obsession with Trump which has captured the imagination of pundits, news media, and bloggers, especially those on the left. The pull is hard to escape—there’s just so much to say about him. There are so many things to criticize; scholars, artists, and comedians are relishing in the opportunity to unload their full critical arsenal. Finally there is a villain deserving our smug liberal heroics. So we enlist in the war of everyone versus Trump. And as so often happens in wartime, we violate the very principles for which we fight. Some of the casualties of 2016 have been objectivity, charitable interpretation, tolerance, a cooperative approach to governance, and even basic respect.  by Russell Johnson Clint Eastwood was in the news this week, not for remaking Denzel Washington’s “Flight,” but for some comments he grumbled angrily during an interview with Esquire. When asked about Donald Trump in an interview, Eastwood said, “He’s onto something, because secretly everybody’s getting tired of political correctness, kissing up. That’s the kiss-ass generation we’re in right now. We’re really in a p**** generation. Everybody’s walking on eggshells. We see people accusing people of being racist and all kinds of stuff. When I grew up, those things weren’t called racist.”  (Photo: DonkeyHotey) (Photo: DonkeyHotey) Welcome to our first ever FTSOA chat! What follows is a free-flowing discussion between Russell, David, and Mike Lehmann, a Republican political operative with a Duke Divinity School degree and friend of the program. This conversation has been slightly edited for clarity. DAVID: I hear lots of people talking about the choice between Trump and Clinton as picking between “the lesser of two evils” and many seem conflicted about doing that. But what is the moral significance of voting for an objectionable presidential candidate? Are you morally on the hook for the candidate’s full slate of positions? Should your conscience hold you back?  Earlier this week, Wayne Grudem endorsed Donald Trump. You may be thinking, “Big deal. I bet a lot of people named Wayne endorsed Donald Trump.” But Wayne Grudem is different. He’s the author of the systematic theology book used by more evangelical seminaries than any other. It’s currently listed as the #1 bestselling Protestant theology book on Amazon.com, and the #1 bestselling systematic theology book. Grudem has been influential among evangelicals for decades now; his writing and teaching form the intellectual backbone of many pastors’ and writers’ theologies. His article, “Why Voting for Donald Trump Is a Morally Good Choice” feels to many of my fellow evangelicals as a betrayal. Though it was scarcely surprising that public evangelicals like Jerry Falwell Jr. and Franklin Graham—whose names are bigger than their influence—supported Trump, it hurts to see  [Originally posted on Facebook on 2/12/16] Dear haters of Beyoncé's Super Bowl performance, No. I'll be more specific. Many people have criticized Beyoncé and her dancers for dressing up in outfits reminiscent of the Black Panthers from the 60s and 70s. So people are upset because Beyoncé is representing a group with a violent history at an NFL game? The same NFL that has a team called the Vikings? And one called the Raiders? And the Buccaneers? And, while we're at it, one called the Texans? But whatever, I'll let it slide. I for one think Beyoncé can reasonably laud the Black Panther Party's commitment to organize against police brutality without thereby endorsing all of the actions taken by its members. But there's room for argument. |

Archives

September 2020

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed