By David Barr Christians often credit or blame the changing fortunes of America on changes in our religious commitments. Some of these theories are nutty: I once heard a guy claim that Hurricane Katrina was punishment for a slackening of U.S. support for Israel at the time. Others aren't nutty, but still pretty strident: folks like Bill O’Reilly and Mike Huckabee have pointed to the end of prayer in schools as the cause of things like school shootings (okay, I take it back; that's still pretty nutty).* More subtly, many Christians point to evangelism as a way to address problems like crime and poverty or credit the Christian religion with successes in our nation’s past. People envision the connection between religion and the fate of the nation in different ways. Some, like the man with the Israel-Katrina theory, see God as directly intervening to bless or smite us in response to our policy decisions. Others see a more naturalistic cause and effect: Christianity makes us better people and a nation thrives when its people are more honest and hardworking, less violent, and so on. However they see it working, it is very common for American Christians to think our current problems are because we have abandoned Christianity. This is a really bad idea, and for a few reasons.

0 Comments

by David Barr Gun control supporters often struggle to understand the fierceness with which gun advocates oppose compromise on the issue. This struggle is understandable: if you think of guns as useful only for hunting or perhaps home defense – with the tradeoff being thousands of avoidable deaths – it is hard to see why anyone would stridently oppose all forms of gun control. It is thus important for gun control advocates to see the extent to which many gun advocates see the right to bear arms as a foundational right – perhaps even the foundational right – on which all the others depend. They will only understand that position if they see the way its roots reach into the myths of the American struggle for independence. It is likewise important for gun rights advocates to see how this belief rests on bad myths about the revolution.  By David Barr White people often get defensive in conversations about race because it can feel to us like being white is always a bad thing. We have to be apologetic: whiteness is something to be ashamed of, not to celebrate. This can seem unfair. Because of this, you often hear people say things like, “If black people can have their own parades/awards shows/advocacy groups/TV networks/whatever else, why can’t we?”  By David Barr When I was young, I became quite enamored with something called ‘apologetics,’ the art of defending the Christian faith against intellectual attack. At the time, it felt like learning Christian nerd karate. My friends and I would read up on things like the ontological argument for God and exchange CDs of debates between apologists and atheists like they were underground mixtapes or bootleg DVDs. Now, I don’t want to come across as dismissive of the very laudable attempt to articulate the Christian faith in an intellectually clear way. It is great for young Christians to learn to think for themselves and to learn how other people think differently. I think this phase was good for me, at least in the long run. Simplifications help young minds learn to think; the danger is when they persist in mature minds. Being Liberal (or Conservative) Is Not an Accomplishment: On the Comfort of Political Polarization7/10/2017 By David Barr We are regularly reminded that our politics keep getting more polarized, and explaining why has become something of a national pastime. People blame social media, 24-hour news channels, or the fact senators don’t take time to smoke cigars together anymore, to name just a few. However, I fear we will underestimate the problem and fail to see its full range of consequences as long as we think of it only as a result of these new developments, rather than as something to which we feel a deep pull. It is not an unfortunate accident that these new factors drag us apart. It is in human nature to divide into camps, to be tribal, to want to see the world in terms of the good guys vs. the bad guys. And while I’m certainly not the first person to make that observation, there is one reason for that tendency that hasn’t been getting much attention: we are drawn toward political polarization because it feels good, because it satisfies our consciences. By David Barr

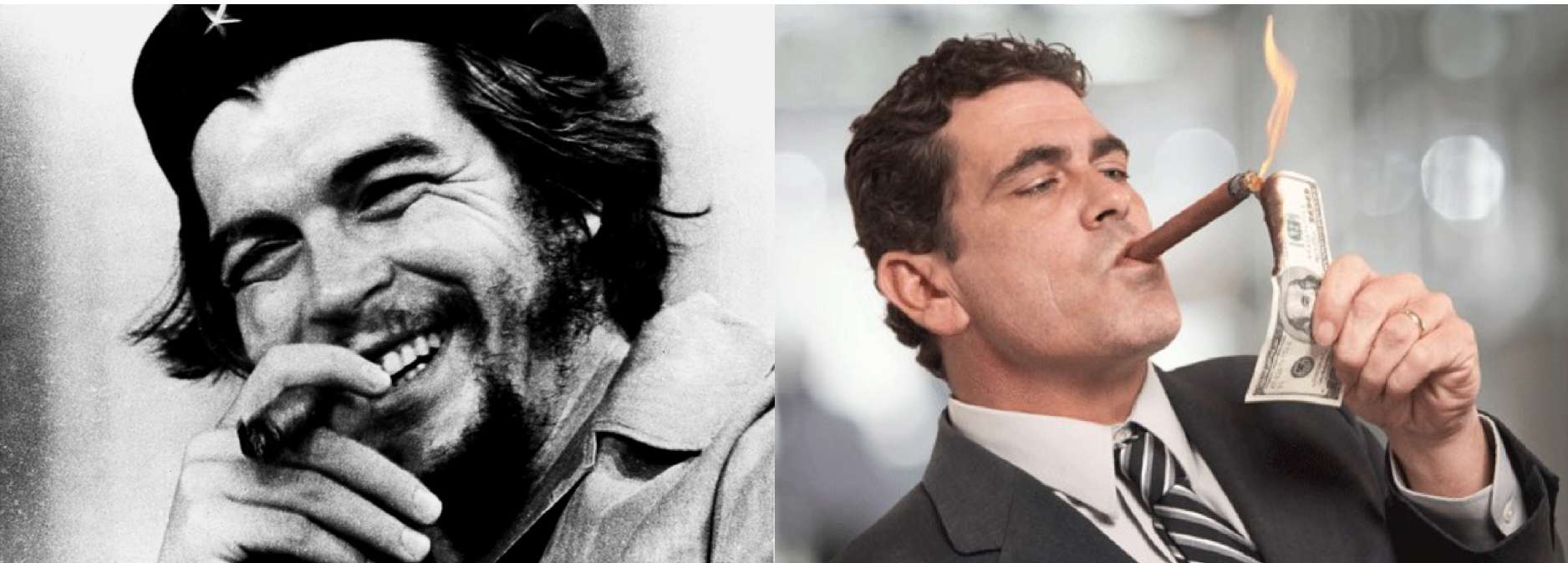

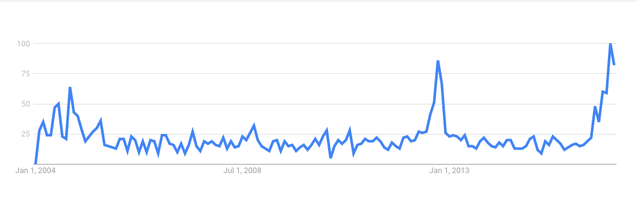

When I prepared to leave the confines of rural, evangelical middle America for the imposing halls of secular, University-of-Chicago middle America, many of my Christian friends expressed grave concerns about the dangerous ideologies I would encounter there. They mentioned atheism, of course, but their main concerns were post-modernism and moral relativism. I was warned I would encounter people who didn’t believe in objective truth, who thought everything was subjective. Now, I did run into a lot of that stuff, especially among students with unruly hair, who smoked cigarettes, used “construct” as a noun, and said things like “Foucault.” Even students with normal hair often told me that what I believed was fine, but that there was no way to really know what was true when it came to things like religion and morality.  By David Barr My sociologist friend, Sam, has a great illustration about the persistent effects of racism: he asks his students to imagine that they are watching a game of Monopoly and one player (let’s say the Thimble) is not allowed to buy property for the first five turns, but does pay rent, while everyone else plays under the normal rules, snatching up several of the best properties. Sam asks his students to imagine they are put in charge of the game after the fifth turn and asks them to think about the best way to make sure the game will be fair going forward.  By David Barr Questions of capitalism and socialism, if they ever truly went away, came roaring back into the public conversation during the 2016 election. With them came misunderstandings about what these terms mean, and about American history. It seems to me that when liberals (particularly young ones) say ‘socialism’, they have something like contemporary Scandinavia in mind; open, educated, democratic, and with the highest quality of life in the world. When conservatives (especially older ones) hear ‘socialism’, they think of the USSR or North Korea: repressive, totalitarian, and with inefficient economies that collapsed under the weight of oppressive government control. This obviously leads to lots of head shaking by each group at the seemingly unreasonable beliefs of the other. That phenomenon is certainly worth a post of its own. Right now, however, I’m just going to use the fact that many conservatives interpret 'socialism' in terms from the Cold War as an excuse to make a point about capitalism and communism. I had been pretty sure that nobody wanted to read what I've been thinking about these old Cold War debates, but they seem relevant now that it is clear that those debates still hang over our current ones. I’m now convinced that taking you on a few minutes’ excursion into the mindset of the 1950s can help bring light to our contemporary political conversations. The lesson of the Cold War, I believe, is that the capitalists and the communists were both right…about each other. Let me explain:  Much has been written about our polarization in values and ideologies, and now much more has been added about our different sources of information and “alternative facts.” This post focuses on another important, but neglected, area of divergence and source of disagreement: the myths we tell that form the context of the values we hold and the facts we accept. My hope is that pointing to myths as an arena of misunderstanding can provide a path forward in cases where agreement and empathy seem impossible.  A reading from the Psalms: "The heavens declare the glory of God, and the sky above proclaims his handiwork. Day to day pours out speech, and night to night reveals knowledge.” Psalm 19:1-2 In at least one sense, science is the original human vocation, a call to share with God in his wonder-filled attention to his creation. In Genesis, we see that as God creates, he calls the different things he makes “good.” When creation is finished and God beholds “everything that he had made,” he declares it “very good.” Then he does something remarkable. He places his final creation—Adam—in the Garden of Eden and gives him a task: to name each creature. Thus, God not only rejoices in the goodness of his creative work, he creates beings who can share in knowing and appreciating it in its particularities. Thus, we see that the original, pure communion between God and man is focused, not in on the relationship between the two of them as individuals, but out toward all creation.  Russell (RPJ): I read an interesting article recently from The Washington Post that explained, better than any article I’ve ever read, one important way conservatives and liberals talk past one another. It’s by David Hopkins and Matt Grossmann, who surprisingly aren’t quarterbacks for the Cleveland Browns. It’s worth reading if you have the time, but I’ll summarize their main point now. If you read the article, feel free to skip this summary. These two professors write that Republicans and Democrats in America think differently not just about the issues, but about how to frame the issues. “Each party’s supporters define the terms and stakes of political competition quite differently,” they write, “Republicans believe they’re battling over two opposing ideologies, while Democrats view partisan conflict instead as a fight between different social groups.” Republicans are more likely to think in terms of conservatism vs. liberalism, socialism vs. capitalism, traditional values vs. postmodern multiculturalism. Democrats are more likely to think in terms of men and women, black and white people, the one percent and the ninety-nine percent.  I recently heard a Christian speaker talk about violence in Chicago. According to him, the answer to the problems plaguing the south and west sides of the city is simple: these communities need to embrace the Gospel. This is not an unusual way for Christians to think, of course, and it might seem to flow from some of the central tenets of the faith. Becoming Christian should make people better, right? If enough people are transformed, that should make neighborhoods better, too. Plus, we look around our churches and see a bunch of (mostly) nice, smiling people who seem unlikely to commit murder. It is only reasonable, then, to think that if we could only bring enough of our neighbors into the Church and into faith, then a host of societal problems would be solved. While I understand the temptation to think this way, I'm increasingly convinced that this is not how Christians should think and talk about social problems.  (Photo: DonkeyHotey) (Photo: DonkeyHotey) Welcome to our first ever FTSOA chat! What follows is a free-flowing discussion between Russell, David, and Mike Lehmann, a Republican political operative with a Duke Divinity School degree and friend of the program. This conversation has been slightly edited for clarity. DAVID: I hear lots of people talking about the choice between Trump and Clinton as picking between “the lesser of two evils” and many seem conflicted about doing that. But what is the moral significance of voting for an objectionable presidential candidate? Are you morally on the hook for the candidate’s full slate of positions? Should your conscience hold you back?  Michelle Obama mentioned in her DNC speech that the White House was built by slaves. Bill O’Reilly then announced on his show that he had looked it up and reassured his viewers that the "slaves that worked there were well fed and had decent lodgings provided by the government, which stopped hiring slave labor in 1802.” People were justifiably angry with O’Reilly over this. It came across like he was saying, “Yeah, ok, I admit the U.S. government used slaves in the past, but it wasn’t that bad and we stopped doing it right away. We can all keep our faith in America’s moral purity.” His comment and the backlash got me thinking about the defensiveness on all sides here. O’Reilly and others of his ilk have very little patience for criticism of America’s past greatness, what they call “revisionist” history. Since America is clearly great, to point out its foibles and imperfections is to obscure the issue, when (to them) America's greatness is clear. Likewise, folks who think slavery and its legacy are a really big deal have very little patience for people pointing out the times it wasn’t so bad. Since slavery was clearly an abomination, to bring up mitigating examples of humane treatment of slaves is (to them) to obscure the verdict of history.  The other day my friend told me something I’ve heard from many Christians over the years. He said, “As a Christian I think it is the church’s job to help the poor, not the government’s.” While this sentence has a nice, reassuring neatness, it is actually a pretty problematic way to talk about politics “as a Christian.” To see why this is the case, consider first the “as a Christian, I think” part of his statement. Now, obviously, we can think a lot of things "as Christians." To name three, we could think that Christians should love their neighbors, that the death penalty is wrong, or that pizza is delicious. It is clear that thinking of them “as a Christian” means something different in each case. |

Archives

September 2020

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed