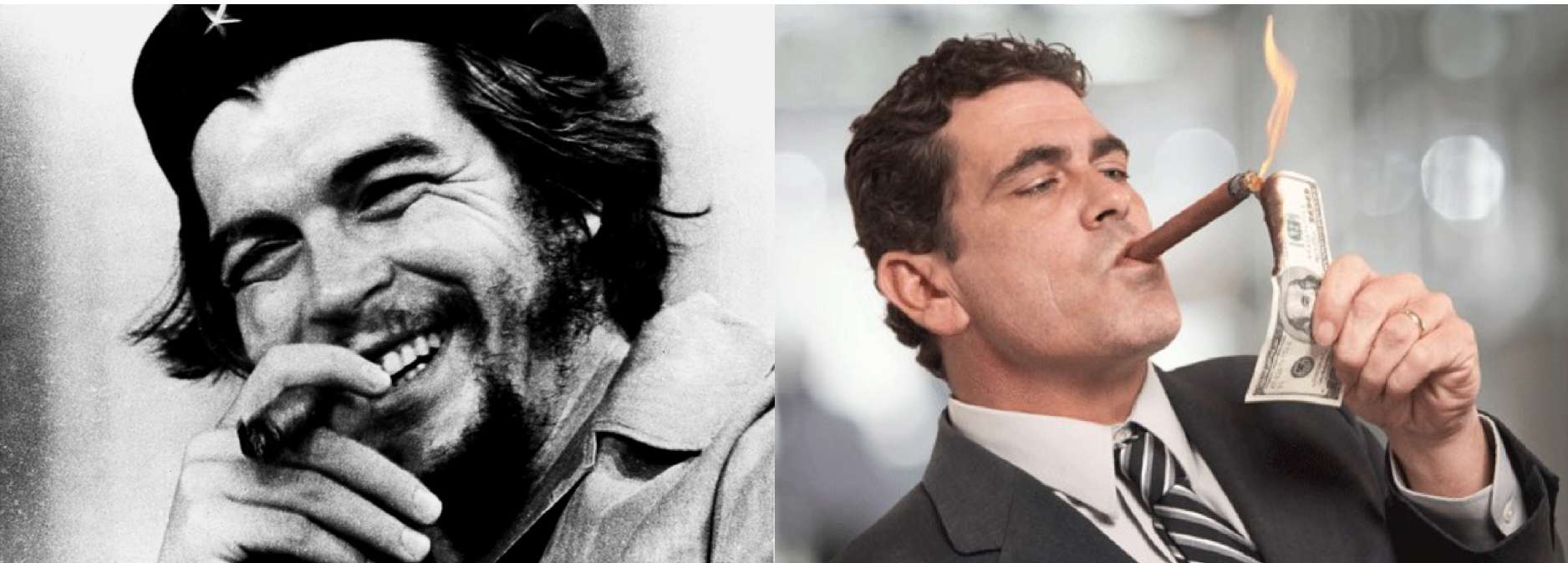

By David Barr Questions of capitalism and socialism, if they ever truly went away, came roaring back into the public conversation during the 2016 election. With them came misunderstandings about what these terms mean, and about American history. It seems to me that when liberals (particularly young ones) say ‘socialism’, they have something like contemporary Scandinavia in mind; open, educated, democratic, and with the highest quality of life in the world. When conservatives (especially older ones) hear ‘socialism’, they think of the USSR or North Korea: repressive, totalitarian, and with inefficient economies that collapsed under the weight of oppressive government control. This obviously leads to lots of head shaking by each group at the seemingly unreasonable beliefs of the other. That phenomenon is certainly worth a post of its own. Right now, however, I’m just going to use the fact that many conservatives interpret 'socialism' in terms from the Cold War as an excuse to make a point about capitalism and communism. I had been pretty sure that nobody wanted to read what I've been thinking about these old Cold War debates, but they seem relevant now that it is clear that those debates still hang over our current ones. I’m now convinced that taking you on a few minutes’ excursion into the mindset of the 1950s can help bring light to our contemporary political conversations. The lesson of the Cold War, I believe, is that the capitalists and the communists were both right…about each other. Let me explain: I study Reinhold Niebuhr, an American theologian who spent his later years as a crotchety old man writing crotchety-old-man books.[1] One commentator (Robin Lovin) described the Niebuhr of that period as a “post-Marxist” and I think this is exactly right. He started out life as an idealistic Marxist in the early 1900s, but then—seeing the horrific violence of communist revolutions—became convinced that communism was fundamentally wrong about human nature. It was too confident that class differences were the source of all our problems and that a classless society was possible. Its unrealistic optimism about the post-revolution world led it to justify extreme violence in the short term. Niebuhr accepted the capitalist argument that an economic system has to work with human greed; it can't simply remove it.

What I love about Niebuhr is that, after his move away from Marxism, he remained a post-Marxist, rather than becoming a blind proponent of capitalism. In other words, while he came to believe that the capitalists were right about communism, he remained convinced that the communists were also right about capitalism. He thought that the communists were wise to see that capital is potentially dangerous (‘capital’ here just means wealth: money, land, etc.). Marxism had become popular in an industrializing world in which the poor worked long hours in dangerous conditions, starting as children, and the only people who benefited from all that work were the ones who owned the factories (the productive capital). The political parties in charge would change, but the rich always exerted enough influence to control the government. Marx thus saw democracy simply as the tool of the rich. It gave the illusion of freedom to the people, while those who owned property controlled every facet of their lives: where they lived, where they worked, what they could buy, etc. In an economic oligarchy, political democracy is a farce. For him, the workers’ only recourse was to seize control of the state and all property in order to arrange the economy for everyone’s benefit. Niebuhr agreed with the first half of that theory: if population exceeds the supply of good jobs and/or available land, the markets will turn against the workers, inequality will rise, and the freedom of the non-rich will disappear. In those conditions, economic power is as oppressive as political power. However, Niebuhr rejected the second half of Marx’s theory. He saw no reason to believe that control by the working class would do anything more for justice than capitalism had. For Niebuhr, people are people, rich or poor, and there is no reason to think that putting power in the hands of a single class (i.e., the leaders of the communist party) would bring about justice. His Christian convictions about sin led him to be suspicious of the claims of any group in power that whatever they do is for the benefit of everyone. He didn’t make a distinction about whether that power was political or economic. He didn’t trust the communist party to arrange the people's lives justly through government, and he didn’t trust the rich (our “job-creators”) to do it through the economy. Now, those readers who are suspicious of any brand of socialism might, at this point, raise an eyebrow and think, “Yes, but America has been thoroughly capitalistic and a land of freedom and opportunity. We have let the economy go and it has benefited the many, not just the rich few. Capital has not been dangerous here.” Niebuhr heard this type of objection a lot and rejected it on two grounds: (1) he disputed the idea that our success was due primarily to our economic system and (2) he rejected the myth that America’s economic system had always been a purely free-market, unplanned economy. About the first, he pointed out that America had been able to provide opportunities to the poor, not mainly because our system guaranteed it, but because we had the space. While European countries had to deal with crowded cities and flooded labor markets, we were able to expand outward, with the frontier acting as a pressure-release valve on overcrowding in the east. If you didn’t like your life in Germany, you didn’t have a lot of options; the owners of capital could drive down wages, increase hours, and raise rent. If you didn’t like your life in New York, you could join the land rush in Oklahoma. In support of his second point, that our system was not unplanned, he raised an issue that we don’t think about enough: the frontier was not an accident. From the Louisiana Purchase to the wars of expansion, we deliberately added to our territory for the expressed purpose of providing capital (land, in this case) to those without it. We intentionally encouraged a more even distribution of wealth because of fear about exploitation. Niebuhr pointed out that, despite our myths celebrating American individualism and free-markets, we have actually been smarter than that in practice. We have spent money and great effort to make opportunities available to everyone. America's westward expansion was, at the time, the largest wealth distribution program in history, a vast project of social and economic design. Money, largely collected from the rich, allowed the government to add territory (through purchases and military conquest) and then give it away or sell it cheaply in order to avoid the social crises that arise from radical inequality.[2] Then at precisely the moment the frontier closed, industry exploded. This, like the frontier, was largely luck: the timing was perfect. However, its benefits were also partly the result of design. We allowed unions, set limits on hours, banned child labor, etc. Once we did these things, all the new industrial jobs allowed people to enter the middle class, buy property, and escape exploitation. This was partly industrialization shifting supply and demand in the labor market, partly policy decisions. Thus, while we have recited a purely free-market mythology, we have been pragmatic enough in practice to make smart choices about the distribution of capital in the economy. We have always used democratic government to influence our economic life in ways that prevent the wealthy few from oppressing everyone else. Niebuhr, at the height of the postwar economic boom and American triumphalism, was wise (and crotchety) enough to see the fragility of our domestic peace. He noted that we had thus far been able to solve all of our potential social problems through relentless expansion of the economy. He saw that we would be in serious trouble were there ever a time when manufacturing no longer offered a path up into the middle class. We would then have to face the social crises that Europe has had to deal with for centuries: low wages, high inequality, the control of government by the rich, and the appeal of populist and authoritarian politicians to everyone else. As dire predictions go, this was a pretty good one. Niebuhr’s Christian post-Marxism offers us a way forward. His advice is twofold: 1) Listen to the capitalists; they were right about communism. We cannot trust a powerful central government to run our economy. This always leads to coercion by the government and all sorts of inefficiencies. We have to protect democracy from authoritarianism. 2) Listen to the communists; they were right about capitalism. We cannot trust a market economy to benefit everyone. Especially in times when labor and housing markets tighten and inequality increases, we have to be alert to the danger that a rich few will arrange things to benefit themselves at the expense of everyone else. We have to protect ourselves from capital. The key, Niebuhr taught, is to forget our free-markets-only myth and to do what we have actually always done: use the power of democracy to promote an economy that allows opportunities for the poor to move into the property-owning classes. We have to encourage (but not mandate) the broad distribution of economic power. What exactly this means for us today is up for debate: perhaps it means investments in public education, infrastructure, housing, and healthcare. Perhaps it means grants to benefit small businesses or consumer financial protections. However, the commitment to do something to restrain the exploitative power of capital does not require that we move toward communisim; all we have to do is continue and expand the long American tradition of pragmatic, proactive efforts to allow the poor space to participate in the life of the country. [3] The job of constitutionally-controlled, limited, and democratic government is to protect us from domination by either authoritarian politicians or unchecked capital. Our government can only serve us if we keep it free from both forms of tyranny. We should all agree on that, whatever our ideology. ****************************************************************************************************************** [1] My dream for my life in a nutshell. [2] I should be clear that, while I’m joining Niebuhr in citing our westward expansion as an example of proactive efforts to shape our economy, I’m not condoning our cruel, dishonest, and violent removal of indigenous Americans. I want to commend our tradition of promoting a diffuse distribution of capital, but not the means we employed. I think we need to be mindful of the fact that our westward expansion allowed us to avoid unpleasant social realities at the expense of other people. If we are now going to face those realities in earnest, we need to be prepared for the possibility that this may require new sacrifices on our part. Other areas where we have traditionally exported our sacrifices include the way we use cheap labor abroad, imbalanced trade agreements, and cross-border pollution, to name but a few. [3] I think this combination of free markets and government efforts to protect the poor from exploitation by the rich just is what many people in the U.S. mean today when they identify as "socialists" rather than "communists." I've resisted labelling this general effort 'socialism' because I hope that conservatives and liberals can agree that this sort of pragmatic protection against exploitation is a necessary part of good governance and a big part of American history. I mean to suggest that we can be vigilant against the dangers of capital without turning to public ownership; there are things like campaign finance laws that help insulate democracy from capital, but don't involve socialist policies. I don't aim to convert liberal capitalists into principled socialists, but only to show that we all need to be wary of the coercive power of capital.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Archives

September 2020

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed