by Russell Johnson Gun control is one of the most frequently talked about political issues in America, but these interactions rarely seem to change people’s minds. This might be true even of the most thoughtful, reasonable discussions, but the gun debate has been characterized by bad arguments that we should never expect to change anyone’s mind. This is often because representatives of one perspective caricature and misunderstand the logic behind other perspectives, so we end up arguing against positions that few people, if any, really hold. The more we rely on these shallow arguments, the more we insulate ourselves in bubbles, making it harder for us to understand one another and harder to seek the truth. In this post, I’ll survey nine all-too-common arguments, from "both sides," that we can safely retire. 1. “_______ causes more deaths per year than guns, so why don’t people ban that?”

I see versions of this argument all the time, especially in images shared on social media. You’re more likely to die from tobacco, alcohol, a car crash, or medical malpractice than from gun violence, the argument typically runs, so why do gun control advocates fixate on guns? Hammers and knives are used in more homicides per year than rifles, or so we are told. So why not ban hammers? Well, there’s a good answer to this question. Hammers and knives and cars all serve valuable purposes, and Americans largely agree that the benefits that come from these tools are enough to justify keeping them legal. There is a ratio between the utility an object has (UO) and the likelihood it will be used to kill innocent people (LKIP), and it is this ratio—not the absolute number of deaths caused—that we take into account when we discuss the legality of objects. We apply this ratio whenever we think about making laws limiting or regulating the possession of items. For example, this is why chainsaws are legal, but not on planes. A chainsaw is useful for cutting trees and logs, so we have no problem with responsible people keeping chainsaws in their sheds (UO > LKIP). But there are no trees on a plane. So if someone has a chainsaw in their carry-on, the probability that they’ll use it to do something bad outweighs the usefulness it could have in that setting (LKIP > UO). The closer the ratio is, the more likely voters and lawmakers are to regulate possession—consider alcohol, tobacco, cars, and prescription drugs. Most people agree that handguns and hunting rifles fit in this category; they can be used for killing innocent people, obviously, but they can also be used for self-defense or hunting. Honest, thoughtful people can disagree about how to weigh these two factors (UO : LKIP) and what forms of regulation are most reasonable, and gun laws are going to end up being the result of a compromise. Given this reasoning—which, again, is not something I’m making up but what people have in mind when they say “common sense gun laws”—we need to confront the possibility that there are some objects whose LKIP is so disproportionate to their UO that they should be very heavily regulated to the point of being extremely difficult to obtain or legally possess. Heroin, for example, fits in this category. The damage it does, both to those who get addicted to it and to those affected by their actions, is vastly disproportionate to whatever utility it may have. There are weapons that fit in this category as well. I have nothing against Elon Musk. But I believe, and federal law agrees, that he should not be allowed to own a nuclear warhead. The likelihood that people could be killed by it far outweighs the utility he’d likely gain from having one. A nuclear warhead is what we’ll label a WWLKIPVOCU, a Weapon Whose Likelihood of Killing Innocent People Vastly Outweighs Its Civilian Utility. In the eyes of most Americans, fully automatic weapons fit into this category, and that is why since 1934 it has been incredibly difficult for civilians to legally own one. Arguments are now being made that the popular AR-15 should be considered a WWLKIPVOCU. Mass shootings perpetrated with AR-15s are evidence that its LKIP is rather high, and given the fact that AR-15s are not particularly useful for hunting or home defense, its UO is minimal. As Former Lt. Col. Ralph Peters recently said on Fox News, “These weapons — AR-15 and similar weapons — are not for sporting purposes,” adding, “The purpose of the AR-15 series weapons is to kill and maim human beings. That’s it.” The same cannot be said of hunting rifles, of cars, of knives, or of hammers, even though these can also be used to murder people. That is why the “these things kill more than guns” argument fails to address the real factors being weighed in gun control debates. 2. Getting overly sloppy with, or overly pedantic about, the use of gun terminology It’s common for advocates of gun control to use terms like “assault rifle,” “automatic weapon,” and “machine gun” indiscriminately, and without attention to the real differences between these categories. This frequently exposes them to ridicule and dismissal from those who are more familiar with guns and know the correct terminology. In general, it’s a good idea to know what you’re talking about, especially when you’re advocating specific legislation. Laws need to be precise, and so should activists, not only to show their readers that they are credible but also in order that careless, reactive laws don’t get passed. That having been said, I suspect that many gun control advocates resort to saying “assault weapon” or “military-style rifle” because they’re looking for a term that expresses what I’m calling a WWLKIPVOCU. We don’t have a word that means precisely that, so journalists grope around for the right words and end up writing articles riddled with mistakes. It’s fair to criticize them for this, but wrong to completely dismiss them. Consider an analogy: a fifteen-foot-long snake is slithering through a library in rural Maine. A librarian is justifiably afraid and calls animal control, saying, “There’s an anaconda loose in the library!” “Actually,” a patron scoffs, “that’s a Burmese python.” The librarian, standing on her desk, replies, “I don’t give a $#!* what kind of snake it is, it doesn’t belong in this library.” In this instance, the problem is a real one even if the librarian doesn’t speak with herpetological precision. Whether the librarian gets all the details right is less important than whether animal control knows how to address the issue properly. A good rule of thumb to apply in gun control discussions is: the more you’re advocating for specific legislation, the more exacting you need to be with your language. A person doesn’t need to know the difference between an assault weapon and an assault rifle to argue that something needs to change in America, and protest to that effect. But if you’re calling for a ban on bump stocks, you should be able to explain what a bump stock is. 3. “Where do you draw the line?” People often resort to slippery slope reasoning when discussing gun legislation. Wherever one tries to draw the line between what should be legal and what shouldn’t be, that line can seem arbitrary. Why this gun and not these others? Why ten-round clips and not another number? Sometimes it can be difficult to draw precise lines between moral and immoral behavior, but when it comes to writing laws, we need standard regulations in place. Take age of consent laws, for example. In Wisconsin, the age of consent is eighteen, and this means that anyone having sex with a seventeen-year-old is committing statutory rape. If a Madison boy who just turned eighteen has sex with his girlfriend who’s only a few days younger than he is, he’s breaking Wisconsin state law. It’s counter-intuitive, perhaps, but for the purposes of the law we have to draw lines somewhere. It’s part of elected officials’ job description to draw lines for legal purposes. Nobody believes that something magical happens to Wisconsonians the day they turn eighteen that suddenly makes them old enough to have sex. But there’s still a logic behind the law—the number eighteen wasn’t just picked out of a hat.[1] Voting laws seem even more arbitrary. Are there fifteen-year-olds who are informed and responsible enough to vote wisely, and fifty-year-olds who aren’t? Of course. But we have to draw a line somewhere, and that somewhere is subject to continued re-evaluation. If someone argued that the voting age should be raised to twenty-one, their proposal is not necessarily the first step down a slippery slope toward nobody voting at all. Nor are arguments for stricter gun laws necessarily steps toward prohibiting guns entirely, or arguments for more lax gun laws necessarily steps toward a country-wide Mexican standoff. Those responsible for writing gun laws have to draw lines between legal and illegal, those lines won’t make perfect sense, and good people will be inconvenienced. The best we can do is make laws that make the most sense, and to do so guided by precedent and expert analysis. 4. “Abortion kills more people than gun violence.” This is a legitimate point, unless one uses it to wave off demands for more reasonable gun legislation. It’s entirely possible to view abortion as a more significant issue than gun violence while still believing that we should take efforts to reduce gun violence. It’s fine to say that the rights of the unborn ought to be a higher priority than gun control, but that doesn’t mean gun control shouldn’t be a priority nor that people are misguided if they focus their attention on gun violence. (I’ve already written about this here, so I’ll move on.) 5. “Criminals will find a way to kill people no matter what the laws are” / “The problem isn’t the guns, it’s human evil” / “Criminals will just get guns illegally” The statement that people can kill without using guns is obviously true. Timothy McVeigh, for example, killed 168 people using a bomb he made from fertilizer, fuel additives, and stolen explosive equipment. In 2014, a group of eight attackers in China killed thirty-one people using only knives. No legislation will ever successfully prevent murder or even mass murder. Visions of utopia need to be humbled by these reminders. But these reminders don’t constitute an argument against stricter gun control. The point of gun control laws, as with almost all laws, is to make it more difficult for people to do the illegal activity. We have laws against drunk driving. Can people still drive drunk? Yes, but they are disincentivized from doing so, and there’s substantial evidence that strict, well-enforced DUI laws decrease the number of fatalities from drunk driving. Similarly, we have laws against the possession of meth. Can people still acquire meth? Yes, but it’s not easy. Let’s imagine I have a terrible day at work and decide to drown my sorrows in bourbon. I walk to the liquor store and buy bourbon, simple enough. Now imagine I decide instead to drown my sorrows in meth. So I grab my keys, put on my jacket, and head out to pick up some meth. What are the odds that I would be successful, against the odds I’d end up arrested or fearing for my life? The difference between the bourbon scenario and the meth scenario is a difference of law. This analogy isn’t perfect, because meth is something ordinary people can make in their basements, whereas semi-automatic weapons for the most part need to be made in factories. Laws are more effective at restraining access to guns than restraining access to drugs because the laws can more effectively shut down domestic production of WWLKIPVOCUs. No law can totally prevent people from killing other people. Strict gun laws won’t ever make it impossible for dedicated, well-connected people to get access to military-style weapons. But these laws might make it more difficult for teenagers to get access to these weapons. This “more difficult” needs to be remembered by those who make utopian projections and by those who dismiss gun laws if they are anything but 100% effective. 6. “You care more about guns than kids” This is a refrain I’ve heard a number of times in the last few months from gun control advocates, especially in the wake of the Parkland shooting. I understand the attitude expressed here, but this slogan doesn’t do justice to the viewpoints of those it criticizes. Those who argue for more lax gun laws genuinely believe that children will be safer if surrounded by vigilant citizens who have the training, experience, and equipment to protect them when an attack occurs. They also believe that people will be less likely to commit violent crimes if they know that civilians around them are prepared to interfere. That is, a well-armed citizenry is an effective deterrent to violent crime and an effective safety net to have in place when violent crimes happen. (See, for example, the “More guns, less crime” hypothesis.) We can and should argue about how realistic these beliefs are, and whether this vigilant, armed citizenry is the kind of country we want to live in. This is an interesting conversation, one that brings up issues of authority, trust, prejudice and fear, the meaning of community, and self-reliance. But it’s the kind of conversation that gets prevented when activists only attack straw men and don’t engage with the competing visions of a safer country that different Americans hold. 7. “Don’t blame the guns” Like point #6 above, this is a straw man argument. No one blames guns for gun violence in any crass sense. Everyone knows that guns don’t kill people, people kill people. The argument for stricter gun control is about limiting people’s access to the means of killing others, so that when people get the urge to kill, their capacity to kill is limited. No one blames the semi-automatic SIG Sauer MCX for the Pulse Nightclub shooting. The question is, had Omar Mateen not been able to obtain that weapon legally, could he have killed forty-nine people and injured fifty-eight others as easily as he did? (More thoughts on the issue of blame can be found here.) 8. Presuming people aren’t sincere in their beliefs, but are only doing the bidding of some larger organization with a sinister agenda I’ve seen this sort of argument a lot. On one side, many point to NRA funding of politicians, declaring that legislators won’t do what they know is right because they’re too dependent on NRA endorsements and donations. On the other side, many see recent gun control activism as a result of government indoctrination of students, or as somehow orchestrated by the same powerful agitators who allegedly pay protesters. We’re often tempted to see collusion and hidden agendas when the more obvious explanation is people agreeing with one another. It’s not the case that these legislators actually believe stricter gun laws will lead to safer schools, but don’t take action because they are being controlled by the NRA’s lobbyists. Rather, the NRA endorses them precisely because these politicians already agree with the NRA, either with the idea that more guns leads to greater safety or the idea that the freedom to own semi-automatic weapons is an inalienable right.[2] You’re free to argue that the NRA and these politicians are wrong about these ideas, maybe even dangerously deluded, but they genuinely believe them and are not simply motivated by profit or political power. The same goes for the March for Our Lives. This was not a stunt staged by George Soros and orchestrated by socialist agitators to use a false pretense to bring down the pillars of American freedom. Those who were marching sincerely believe that reforming gun laws in America will make America a better country. There’s no hidden agenda; people just want safer schools. You’re free to argue that the laws they’re proposing are counter-productive and will lead to greater loss of life, or that they fail to recognize that further gun regulation will push us over a tipping point toward dictatorship. But they genuinely want people to be safe, and they don’t believe these laws trample on fundamental rights any more than the existing ban on fully automatic weapons or the prohibition of guns on flights does. Here’s a general rule: rather than inferring insincerity and seeking to expose it, give people the courtesy of believing they’re wrong. 9. “Instead of changing the gun laws, what we ought to be focusing on _________” There are a lot of ways to fill in the blank. Mental health. Bullying. Racism. Culture. Capitalism. Toxic masculinity. Over-prescription. These are all valuable topics worth addressing. But, like #4 above, we create a false dichotomy when we treat these issues as mutually exclusive. If you say, “We need more reasonable gun laws” and I respond, “We need kids to be kind to each other,” I’m not arguing with you, I’m just changing the subject. That’s part of what’s so strange about the “Walk Up, Not Out” response that emphasized anti-bullying efforts—where does this “not” come from? When Rick Santorum says that we should focus instead on training kids in CPR, why is this an “instead”? Imagine if I ran a restaurant, and I told my employees I don’t want anyone to get sick, so they all need to wash their hands regularly. Someone chimes in, “Instead of washing your hands to prevent disease, we should exercise and take vitamin C and zinc to keep our immune systems functioning.” My response would be “Okay, do that stuff, but WASH YOUR HANDS TOO.” This is how gun control advocates feel when they are dismissed with these false dichotomies. It’s certainly the case that gun violence in America is a multifaceted problem and that no one solution—legislative or otherwise—will be sufficient to address it. But arguments like these rest on the false assumption that the need for non-gun-control ways of addressing gun violence counts as a case against gun control. __________ We need to retire these nine arguments—not because gun laws in America are impossible for people of different political views to think through together, but because there are shared concerns, systemic issues, and troubling facts about guns in America that we desperately need to be talking about. These nine superficial, dismissive moves get in the way of sustained engagement with these deeper questions. Here are a few questions to start more constructive conversations about gun laws and gun culture in America:

[1] It’s obviously in honor of Green Bay Packers #18, Randall Cobb. [2] Even as I write this, I recognize the reality is more complicated. For a deeper investigation that complicates my point, see “The Case for Motivated Reasoning” by Ziva Kunda. [3] In the film Captain America (2011), Stanley Tucci’s character says, “So many people forget that the first country the Nazis invaded was their own.” This domestic invasion, and the possibility of it happening in America, is often alluded to in NRA literature.

1 Comment

Terrific analysis of these logical fallacies! I conducted a teach-in on March 14 at the Christian liberal arts college where I am a faculty member. Although I have been teaching non-violence for a few years, I found I needed to do more research on various types of guns (names, capacity, history, price, etc) in preparation, and it opened my eyes to this potential weakness in my approach. Your observations are right on, in my opinion-- and that's not only because I am strongly sympathetic to what you're after. I think we agree that discussions that gently but firmly lay down these arguments open up rather than restrict paths to reconciliation. Please keep writing these superb essays. Thanks.

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

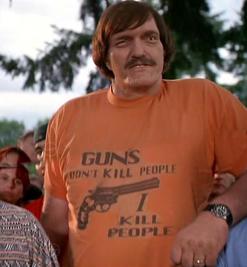

Archives

September 2020

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed