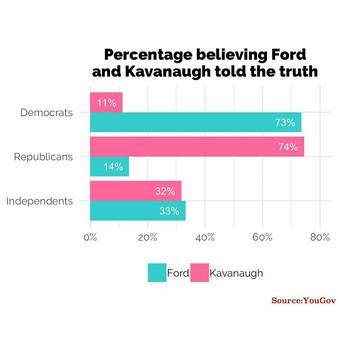

by Russell Johnson People who work for political depolarization, as I do, get quizzical looks from people who focus primarily on other social issues. Republican-versus-Democrat, after all, is not as significant as gender, race, class, religion, worldview, or culture. More often than not, the dichotomy between "liberal" and "conservative" conceals more than it reveals. While I don’t want to make the Brett Kavanaugh drama about myself, this week’s events provide me with an opportunity to explain why I study and write about political polarization. When we hear about a new event, our first impression depends on which series of events we interpret it as being part of. One may go on to revise one’s interpretation as one accumulates more evidence, but often evidence serves to confirm the narrative one initially uses to make sense of the event. What you find plausible depends on how you initially categorize an event.  For example, say one day I can’t find my wallet. I recall a pattern of robberies in my area, and I immediately interpret the event as a theft. My wife, however, recalls a pattern of my own absent-mindedness, and immediately interprets the event as me misplacing my wallet. We both jump to tentative conclusions, and then look at the facts to test our hypotheses. Which conclusion one jumps to depends upon how one frames the event, that is, which pattern one sees it as the latest instance of, and this initial framing can play a big role in determining what one ultimately believes. There are many patterns people use to interpret Dr. Ford’s testimony, among them: (1) a victim, silent for years, courageously coming forward out of civic duty, (2) a troubled person seeking attention, money, or revenge by lobbing false accusations, (3) a politically correct feminist making a big deal out of teenagers being teenagers, and (4) part of a ploy by the Democrats to discredit Trump’s nominee in order to gain political influence. There’s lots of valuable research and advocacy being done on why people believe or disbelieve (1), (2), and (3). Gender dynamics, rape culture, structures of silencing, effects of trauma, mass media, sexual ethics—all of these are crucially important to making sense of Dr. Ford’s story, Judge Kavanaugh’s reaction, and Americans’ responses. I’m grateful to the many people who know more than I do about these topics, from research and experience, who are bringing passion and clarity to the conversations surrounding these hearings. (see, among others, these three links) The work that I do focuses specifically on why people believe (4). Why do so many people immediately conclude that a political party is knowingly trying to obstruct and deceive? Where does this pervasive mistrust of political opponents come from and what can be done about it? What narratives are people using to frame events, what truth is in these narratives, and what other frames might be more conducive to understanding? How does political conflict become so all-consuming that more and more gets interpreted through the lens of partisan competition, and what effect does this have on our relationships, our theologies and ethics, and our ability to discern the truth? The question of Kavanaugh’s guilt or innocence is not a Republican-versus-Democrat question, but millions of people painted it in red and blue before they learned how to say “Blasey.” Even if you don’t think Republican-versus-Democrat is a helpful way of thinking about things—maybe especially if you don’t—it’s worth paying attention to how these two “sides” and the mistrust between them get mobilized to influence how people think.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Archives

September 2020

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed